Next, Logging, and Conclusions

Welcome to Part 6, the final installment in this series. Below we cover unit testing the noop next, how to create pure functions that wrap noop so you can compose them, and finally using code coverage to strategically hit the last code that’s not covered.

Contents

This is a 6 part series on refactoring imperative code in Node to a functional programming style with unit tests. You are currently on Part 6.

- Part 1 – Ground Rules, Export, and Server Control

- Part 2 – Predicates, Async, and Unsafe

- Part 3 – OOP, Compose, Curry

- Part 4 – Concurrency, Compose, and Coverage

- Part 5 – Noops, Stub Soup, and Mountebank

- Part 6 – Next, Logging, and Conclusions

Next is Next

The last part is deal with next. THIS is where I’d say it’s ok to use mocks since it’s a noop, but you do want to ensure it was called at least once, without an Error in the happy path, and with an Error in the bad path.

… but you’ve made it this far which means you are FAR from ok, you’re amazing. NO MOCKS!

Here’s the basic’s of testing noops. You sometimes KNOW if they did something, or how they can affect things based on their arguments. In next‘s case, he’ll signal everything is ok if passed no arguments, and something went wrong and to stop the current connect middleware chain if an Error is passed, much like a Promise chain. We also know that next always returns undefined.

Ors (Yes, Tales of Legendia was bad)

One simple way is to just inject it into the existing Promise chain we have:

.then( info => next() || Promise.resolve(info))

.catch( error => next(error) || Promise.reject(error)))

This’ll make the connect middleware happy as well as satisfying our unit tests expecting either an email info out, or a rejected promise with error.

Pass Through

Much like you log Promise or other Monad chains, simply make a pass through function.

const nextAndResolve = curry((next, info) => next() || Promise.resolve(info))

const nextAndError = curry((next, error) => next(error) || Promise.reject(error))

And since we already know what the next is, we can just attach ’em to the end of the Promise chain, similar to above:

.then(nextAndResolve(next))

.catch(nextAndError(next))

“Wat!?” you may be saying, “all you did was wrap that previous example in functions”. Yup, they’re pure, and you can test those in isolation vs. test that gigantic Promise chain with 20 billion stubs.

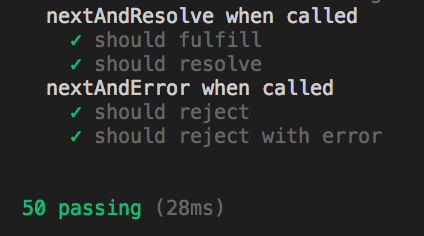

describe('nextAndResolve when called', ()=> {

it('should fulfill', () => {

return expect(nextAndResolve(noop, 'info')).to.be.fulfilled

})

it('should resolve', () => {

return expect(nextAndResolve(noop, 'info')).to.become('info')

})

})

Let’s do the same for error:

describe('nextAndError when called', ()=> {

it('should fulfill', () => {

return expect(nextAndError(noop, new Error('they know what is what'))).to.be.rejected

})

it('should resolve', () => {

const datBoom = new Error('they just strut')

return expect(nextAndError(noop, datBoom)).to.rejectedWith(datBoom)

})

})

If you’re Spidey Sense left over from your Imperative/OOP days is tingling, and you really want to create a mock or spy, go for it.

I would rather you focus your time on creating pure Promise chains vs. investing in better testing side effects using the connect middleware.

Mopping Up

Only 2 functions to go, and we’re up in dem hunneds 💯.

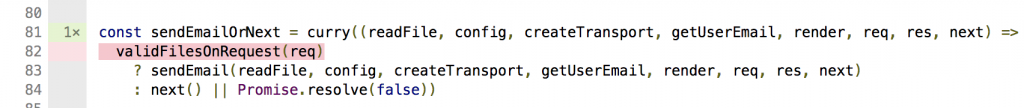

sendEmail … or not

The sendEmailOrNext is a textbook case of copy-pasta coding. We’ll duplicate our previous sendEmail unit tests since they have some yum yum stubs:

describe('sendEmailOrNext when called', ()=> {

...

const reqStubNoFiles = { cookie: { sessionID: '1' } }

...

it('should work with good stubs', ()=> {

return expect(

sendEmailOrNext(

readFileStub,

configStub,

createTransportStub,

getUserEmailStub,

renderStub,

reqStub,

resStub,

nextStub

)

).to.be.fulfilled

})

it('should fail with bad stubs', ()=> {

return expect(

sendEmailOrNext(

readFileStubBad,

configStub,

createTransportStub,

getUserEmailStub,

renderStub,

reqStub,

resStub,

nextStub

)

).to.be.rejected

})

it('should resolve with false if no files', ()=> {

return expect(

sendEmailOrNext(

readFileStub,

configStub,

createTransportStub,

getUserEmailStub,

renderStub,

reqStubNoFiles,

resStub,

nextStub

)

).to.become(false)

})

})

I’ve left out all the stubs, save the new one that shows, if we have no files, it just bypasses the entire thing, calls next with no value signaling to connect we’re good to go and finished, but still returning a useful value of false to say we didn’t do what we’re supposed to since we couldn’t find any files.

There And Back Again

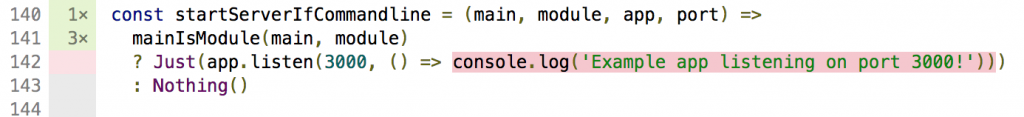

Oh look, coverage found yet another noop, imagine that.

const logPort = port => console.log(`Example app listening on port ${port}!`) || true

And the 1 test:

describe('logPort when called', ()=> {

it('should be true with a port of 222', ()=> {

expect(logPort(222)).to.equal(true)

})

})

Should You Unit Test Your Logger!?

If you really want to create a mock/spy for console.log, I admire your tenacity, Haskell awaits you with open arms in your future. Remember me when you’re at the top and you’ve bested Mr. Popo on the Lookout.

… however, if you’re not using console.log, and instead using a known Node logger like Pino, well, heh, you SHOULD!

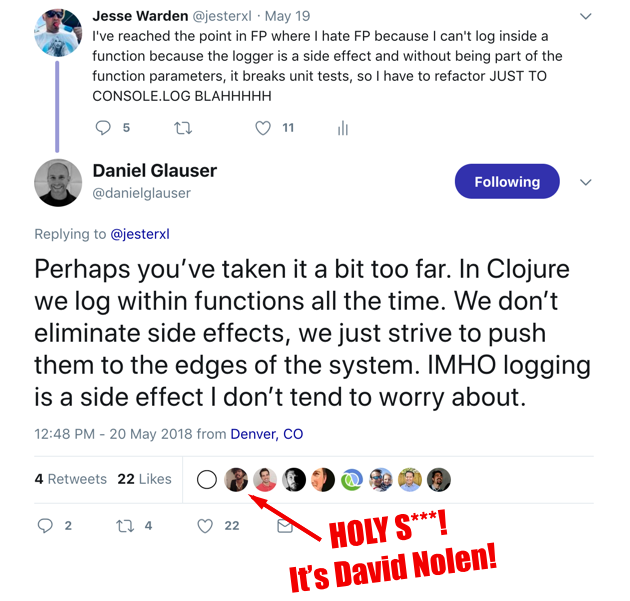

I should point out some well known Clojure guys think I’m going overboard:

If you read the Twitter thread, an Elm guy schools me, and the Haskell cats show me how even there you can trick Haskell, but still acknowledge (kind of?) the purity pain.

Conclusions

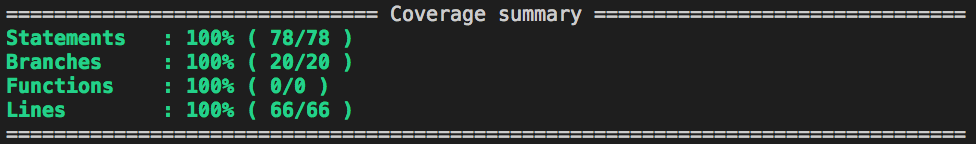

Running coverage, we get:

Welcome to hunneds country. Congratulations on making this far, and not one import of sinon to be found. Don’t worry, deadlines and noops are all over the place in the JavaScript world, and sinon’s mock creation ability is not something to be shunned, but embraced as a helpful addition to your toolset. Like all technical debt, create it intentionally with notes about why, what to remove, context around creating it, etc in code comments around it.

Hopefully you’ve seen how creating small, pure functions, makes unit testing with small stubs a lot easier, faster, and leads to more predictable code. You’ve seen how you can use Functional Programming best practices, yet still co-exist with noops in imperative code, and classes and scope in OOP.

I should also point out that writing imperative or OOP code like this is a great way to learn how to write FP. Sometimes our brains are wired to flesh out ideas in those styles, and that’s great. Whatever works to get the ideas down. On the front-end, using vanilla React’s classes vs. recompose… or even just components functions only. Functional Programming will still hurt just as much as Imperative or OOP if you’ve got a not-so-figured out idea on how some problems should be solved and structured. Write it so it feels comfortable, the refactor & test to purity.

You’ve seen how to compose these functions together synchronously via operands like && and ||, using flow/compose. You’ve also seen how to compose them in Promise chains and Promise.all, curried or not.

You’ve also seen how 100% unit test coverage in a FP code base still has bugs that are only surfaced with concrete implementations using integration testing, such as with Mountebank.

Node is often used for API’s that have little to no state and are just orchestration layers for a variety of XML SOAP, JSON, and text. The no mutable state of Functional Programming works nicely with that concept in ensuring those no state to debug.

Conversely, if you’re dealing with a lot of state such as database connections and streaming text files, not only can you see how you can test such challenging areas using pure functions, but also how many of those things can be run at the same time to speed things up with stepping on each other through global variables.

Props to Cliff Meyers for teaching me what Mountebank is.

Code & Help

The Code is on Github. Got any questions, hit me up on YouTube, Twitter, Facebook (I’m Jesse Warden), or drop me an email.