In this article we’ll cover a basic Effects As Types example; using types in TypeScript to represent side-effects. We do this to help ensure our code works, leveraging the compiler for fast feedback, and simplifying our unit tests. By the end you’ll understand how you can leverage the compiler to assert important side-effects happen instead of using spies.

I was inspired to write this because we’re dealing with testing Observability at work, and this article from Pete Hodgson describing the architecture and testing of Observability code in your Domain logic, that is quite good. I noticed the lack of types as a tool to help here, so wanted to add a simple technique that can help make testing easier.

Why Care

First, let’s cover why spies should be avoided, what they are if you’re not aware, and what side-effects are so you understand the problem we’re solving here.

Spies in unit tests should be avoided, and side-effects should at be tested with both types and Acceptance Tests, giving you confidence your code works as intended. This is nuanced depending upon programming language, but with TypeScript, we’re at a point where the types are good enough you don’t need to use spyies anymore in unit tests for the side-effects and can use types instead.

What’s Wrong With Spies?

Spies break encapsulation by knowing how your code works. This can discourage refactoring because even if you don’t change behavior of the code, it could break the tests. This in turn creates both the inability to easily refactor code and also creates a negative perception of the unit tests (e.g. tests break even though your code still works). You also have more state to remember in your unit test suite (e.g. beforeEach/afterEach). Finally, it increases the amount of code needed to code, read, and maintain in the unit tests.

My background is in Functional Programming with good type systems; there, everything returns a value, and you can use this typed value as part of the function signature to ensure “it’s doing the side-effects it needs to be”.

Why Even Use a Spy?

When writing tests, we often have side-effects in those tests that are important. If everything was just a pure function, our program wouldn’t actually do anything beyond warm a CPU; side-effects are what do important things in the real world. However, they often don’t return any value; the effect itself can happen outside of your program (e.g. logging to standard out, making a database update, etc).

It’s also common in Object Oriented Programming to encapsulate those effects as part of your abstraction. When these best practices were being created, good type systems weren’t in those languages, so types didn’t play a part in “design”; testing and architecture patterns did. Therefore many class methods will do mutation and other side-effects, and return nothing or void. You’ll continue to see that in both older blog posts/books & new, including many LLM’s.

Thus most testing literature will encourage, like us, that testing these side-effects is extremely important. How do they that is typically with what Gerard Meszaros calls “Spies”. After the code under test runs, you can then ask this spy “Were you called with the data we expect?”. This gives you confidence the code did it in fact call the side-effect full code in a way you expect.

Moving From Spies to Types

Let’s first show how a unit test is currently using a spy. Then we’ll move it towards using types.

From Spy

This code does some business logic and logs the result for Observability reasons (e.g. alerts in Honeycomb or Splunk or New Relic) with associated unit test that uses a spy.

function itsTheBusiness():BusinessResult {

const result = doTheBusiness()

console.log({ message: "business", result })

return result

}Code language: JavaScript (javascript)There are 2 unit tests; 1 validates the result that itsTheBusiness returns. We’re interested in the 2nd test; the one that validates console.log sent our message to ensure our Observability, e.g. our alerts in Honeycomb, continue to work.

it('should send the business result to logs', () => {

const consoleSpy = vi.spyOn(console, 'log')

const result = itsTheBusiness()

expect(result).toBe('cow')

expect(consoleSpy).toHaveBeenCalled()

});Code language: JavaScript (javascript)This spy is required to be setup to test the code, and it “knows” a console is used, and that it uses the log method. If we comment out the console.log, the test fails, ensuring we log the result.

To Types

The type signature says that this function returns a BusinessResult, but it’s also doing some logging, so isn’t telling teh whole store of what this function does through the type signature. Currently, console.log doesn’t return anything useful; undefined doesn’t tell us it worked or what the data was.

We’ll assume console.log is a safe side-effect; meaning it always works, but is a side-effect. Examples include Math.random() and new Date(); non-deterministic, but won’t crash your program like fetch or fs.readFileSync. The difference is unlike console.log, both of those have return values.

Let’s create a light wrapper to fix that.

First, a type:

type LogMessage = { logMessage: any }And second, a lightweight wrapper:

function log(logMessage:any):LogMessage {

return { logMessage }

}Code language: JavaScript (javascript)Now that our logger has the ability to return a useful return type, we can leverage that type by updating the itsTheBusiness function contract: You must return a BusinessResult AND a LogMessage.

// this...

function itsTheBusiness():BusinessResult

// ... to this

function itsTheBusiness():[BusinessResult, LogMessage]Why is that subtle change important? Ask yourself “Where do I get a `LogMessage1?”

You get it from calling log. If you don’t call log, then you don’t have a LogMessage. If you don’t have a LogMessage, you can’t compile 😊. This ensures compiling means your code is working as expected; the types help enforce that.

Let’s see what that looks like in practice. We’ll change our code to fulfill that new type signature:

function itsTheBusiness(): [BusinessResult, LogMessage] {

const result = doTheBusiness();

const logMessage = log({ message: 'business', result });

return [result, logMessage]

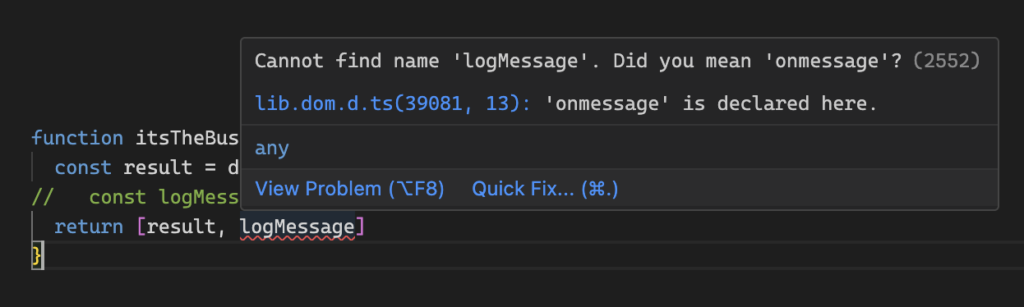

}The test still passes… ok, not much interesting there, just more to read. Watch what happens when we comment out the log call:

You see the compiler won’t let you compile; you need a LogMessage and the only way to get it is to call log.

Finally, let’s clean up the unit test by removing the spy:

it('should send the business result to logs', () => {

const [ result ] = itsTheBusiness()

expect(result).toBe('cow')

});Code language: PHP (php)No more spy, but still ensures you’re logging is happening.

Conclusions

Spies are a way to assert methods/functions are being invoked in ways you expect. They are useful in programming styles where you have side-effects and want to assert those interactions are happening as you expect. Vitest improves this by making them type-safe.

However, they also have too many negative tradeoffs: they know how the code works, what dependencies they are using, and how those dependencies are used. This requires you to setup those spies and tear down those spies in unit tests. This is more state to manage in unit tests, more code to write, read, and maintain. This also creates a negative incentive not to refactor your code because you may break the tests despite the code itself not breaking.

We should continue to use Acceptance Tests to validate our side-effects happen the way we expect. However, types can also help shift the problem left, and add the “when it compiles, it works” mantra to add a level of confidence our code does in fact work along with the Acceptance Tests. This leverages both types and tests to move towards fearless releases.

We’ve used a type for a log message, but this can apply to any side-effect you deem important, and start notice you start reaching for a spy. Instead, you can model those effects as types, and ensure they’re used the way the side-effect should. There are many other benefits of this approach we didn’t cover, having side-effect types as values. Hopefully this gives you a taste of their benefits.

Leave a Reply