Introduction

On my last project, I managed a team developing an application to manage hospitality locations. Given our requirements were constantly in flux, the contracts were on a short cycle, and the team was generally new to enterprise software development, I chose a Kanban style approach to managing and delivering it. I wanted to share with you the rationale, methodology, challenges, and the surprising change to my role while on the project.

Why Kanban vs Scrum?

Scrum has too many meetings, requires a well groomed backlog, and assumes senior developers so that they can accurately task & plan their stories.

Junior to Mid-Level Team

Given I was running my mid-level team in an Enterprise setting, I knew others would be more than happy to sabotage our teams productivity with meetings of their own. Part of the solution, not part of the problem. New team members, both onshore and offshore, who I expected to be reasonably cross functional whether they liked it or not, needed all the time they could to focus and learn quickly.

No Solid Requirements

Given staffing was changing bi-weekly with an my on-going effort to teach the Subject Matter Experts (SME’s) turned Business Analysts (BA’s) how to create properly groomed stories, there wasn’t anything the team could commit to within a reasonable timeframe. For example, it took us 8 workshops over 3 weeks to get to a solid understanding of what we thought we were building.

No CICD

We also had no build nor DevOps in place to facilitate Continuous Integration and Continuous Delivery. Thus we had no ability for weeks to deliver a working, high quality feature because there was no build to allow Developers & Quality Assurance to verify quality, nor server to deploy it to.

No Roles, Just Fullstack / Cross Functional

Having a Product Owner assumes you have someone either in Business, or who represents them, that knows what to build. The client asked us to use our expertise to help them out in true Consulting style. Thus there was no Product Owner.

There was no need for a Scrum Master. Sprint Planning was pointless because we couldn’t plan 1 to 2 weeks in advanced since high level Epic’s were still being both defined, priced, and architecturally validated. For months. I already knew what the team was working on, and so did they, by their small Trello cards. If people had blockers, they asked me or the team over Slack and we collectively resolved it. There was no need for Retrospectives because there were no Sprints since things changed daily so you couldn’t effectively reflect on what happened the past week because it was ever changing. There were no roles beyond everyone coding the client, server, and some of the DevOps together.

Scrum would of been lot of ceremony with no value.

Enter Kanban

What Kanban does well is allow you to change quickly, allow the team to be productive despite the chaos, with a continuous flow of delivering working software that’s in sharp contrast to the insanity outside their productive world. Unlike Scrum, you much more quickly visualize the work going on “today” and identify problems sooner than later. Since the work in progress tends to be smaller, you can flush out bottlenecks in the process sooner. You can create swimlanes and also identify which ones have bottlenecks.

Flexible to Ever Changing Direction

As each new day brought in new or modified requirements, role changes, and improved DevOps and API offerings, I would change the Backlog to match “today”. Given we had no build, nor DevOps starting from scratch, I had a lot of flexibility to inject more build specific tasks so as to keep away from Yagni until we got a solid enough user story. “No user stories, nor API? No problem, get Mocha working with our Node code.” I’d attempt to stay 1 to 4 days ahead of my team. This was to ensure they were working on what I knew at the time to be real and providing client & user value.

Productive Despite Chaos

Politically, it helped ensure we were being productive and thus visually showing we’re using the client’s money effectively with the fast ability to change course if they wanted something changed faster than a Scrum Sprint would typically allow. This happened often.

Learning the Team’s Strengths, Weaknesses, and Desires

I had a new, junior to mid-level Development team and QA team, on a greenfield client (meaning no existing infrastructure or code), with ever changing requirements, staffing, and contract lengths. Since the team was new and learning the entire Software Development Lifecycle whilst me doing my best to shield them from politics, lack of a CICD process, lack of requirements, and nothing pre-built for them via Yeoman generators / starter projects… I knew things would be slow and unpredictable at first.

What I didn’t know was the team. I didn’t know their strengths, weaknesses, and most importantly, desires. Happy developers are productive developers. A lot of people say they are fullstack to ensure they are employable or because they are insecure that their speciality skill set cannot stand on it’s own. That or they like working in smaller, more cross functional groups.

As much as I expected the team to touch all parts of the development stack, including myself, you always have people who naturally gravitate somewhere, or like to be pushed to a particular area like API’s, services, components, or build level tasks. This should be encouraged just as much as being cross functional to get the most out of them, and the team. Additionally, as the project matures, you have less of a need to be cross functional as often, and tend to see people dive deep over time.

Creating Tasks in Trello

I also didn’t know the team’s ability to estimate their own tasks. It didn’t matter since the user stories weren’t defined enough for them to do so. Thus, I broke all tasks down for the team and included additional DevOps and QA tasks as well into small units. We used Trello, a real-time collaborative project board full of cards, to keep track of the work.

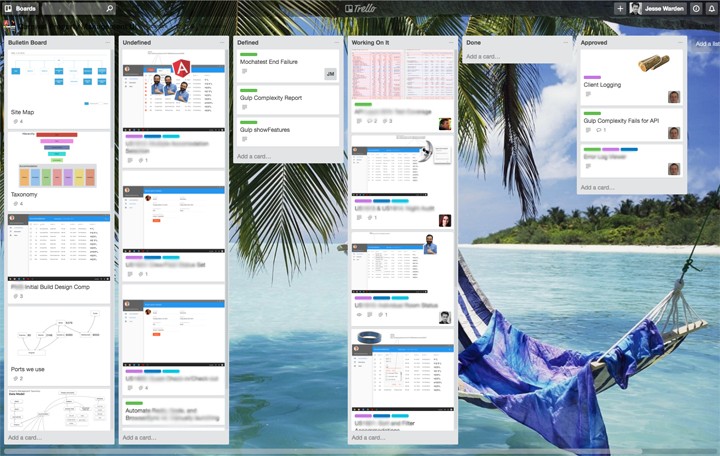

We had 6 columns in our Trello board, from left to right:

- Bulletin Board: All the documents & images for our project

- Undefined: Stories & Tasks I didn’t have enough clarity on for the team to work on.

- Defined: Tasks I fleshed out enough to ensure anyone on the team could work on with clearly defined success criteria, easily merged into a Github Pull Request, and colored with the swimlane it belonged to: Testing, Client UI, Node API, DevOps, and UX.

- Working On It: What tasks were being actively worked on in the team. I ensured only 1 card per developer

- Done: For tasks that were done and developer tested, but not QA approved via them manually testing the Card’s associated PR.

- Approved: QA approved PR’s that merged into the dev branch and deployed via Jenkins Docker build.

Observe the Flow of Development…

What happened next sold me on one of the key strengths of Kanban.

Every day I could immediately see problems. Instantly. It happened just like Andrea Ross said it would, and I’d see where bottlenecks were in the process. Each column in Trello would suddenly get overflowed with cards. You could be near blind, simply squint at the board so you couldn’t actually read anything and STILL SEE IT. The size of the columns told all: you have a bottleneck somewhere here.

It’s called Cycle Time: how long a piece of work goes from left to right. You want to ensure once cards are created, they speed from Undefined to Accepted (left to right, start to finish) as quickly as possible. Typically that process isn’t linear; SOMEWHERE in the journey there is always a bottleneck.

… Adjust as Necessary

How do I know I’m done?

The first one was the success criteria I gave wasn’t clear enough. 90% of my created cards in Defined were moved back to Undefined by the team. Once I gave better success criteria, the development team started to chew through them. I wouldn’t hear from them for hours, then cards would suddenly start piling up in the Done column w/PR’s to boot.

What does the UI look like?

The second one was lack of good wireframes and designs to illustrate both the layout and interactions of how the UI worked. We didn’t yet have budget for a UX resource, so I spent the time myself building low fidelity wireframes that were as accurate as possible and then creating design comps matching our Material Design style guide. I ensured all new cards had relevant design artifacts attached. If the wireframe/design comp changed, I’d move the card from Defined back to Undefined to ensure the team didn’t touch it. If it was too late, I’d create an iteration card to modify an existing piece of work with the updated UI/functionality change.

How do I test it works?

The third one was the inability for QA to test functionality as cards started piling up in the Done column. QA didn’t yet have the build running locally, nor a QA environment to test on, nor a set of tools to help them automate it, nor a lead to help mentor them towards this.

So I picked up the torch, implemented Angular’s Protractor with the Cucumber version, then had a team member get an actual working feature through Gulp. I then worked with the QA team and BA’s to help define better Cucumber features through workshops so they were easier to test. I attached these as additional artifacts to each card where applicable.

Finally, we started Dockerizing our build to use through Kitematic & DockerHub. Given how hard it was to get Redis + Node working the same between the Developer’s Macs and the QA’s Windows machines with various lack of admin rights, this helped ensure things actually worked, quickly, without debugging install or configuration issues.

Continually Improve

This process never stopped. Sometimes it was small bottlenecks or even just blockers and we’d do our best to improve the process. Despite the politics, climate of unknowing, and constant readjustment of requirements & processes… it felt good to be making both progress and improving the process.

Developers got to zone out by donning headphones to jam on code all day. Working code continually emerged as long as I fed this process.

We almost got to the point where the developers had no clue about the ever changing conditions on the ground with the client, ignored it when I brought it up, and focused strictly on questions about specific tasks. I’d call that a process win.

Challenges

It wasn’t all rose colored glasses.

The Importance of Good, Upfront DevOps

The main pain point throughout the entire process was our DevOps starting late in the cycle. Without a good CICD process, Scrum and Kanban don’t really seem to work all that well in tracking “actual work” because no actual work… works. Now, the CIÂ portion we knocked out of the park ourselves and quickly while waiting for confirmed requirements using Github and Jenkins in Docker + AWS. Mostly. The CD, however, took awhile.

What we wanted at first was once a PR was approved, the code would, after a successful Jenkins build, deploy a Docker container of our code to a publicly accessible Amazon Web Service (AWS) instance. It took us about 3 months to get that going given our resource constraints & timing. In the interim, we did a lot of mocks and testing on localhost with ngrok for demos.

Once our Docker deployment was working we started having code be deployed without our knowledge in a good way; the development team just focused on completing cards, and eventually the QA would focus on verifying manually what made it through the automated QA process to the server matched up.

The latter took forever simply because I was stretched too thin running the Development team, helping the DevOps team, doing my own wireframes and design comps, mentoring the BA’s to write awesome user stories via Behavioral Driven Development to minimize our story grooming sessions, and keeping Senior Management in the loop.

Even with Analysts starting the DevOps, it’s clear having them full time on that endeavor payed off big time. In the future, I’m curious if I’d rather focus on that full time myself since it seems to have the largest, cross team impact regardless of whether the requirements, UX, and CIÂ are in a good or bad spot.

Wireframing & Designing at the Same Time vs. Staggered

While me being the same person to do the wireframes made it easier to build design comps around them, it simnifically reduced the time I could spend with other teams. When the Undefined column would get too full, I’d have to spend the early part of the week ensuring I had enough information to wireframe. I’d then spend the weekend on the design comps and then break them down into easily tackled, small PR tasks in Trello. This wasn’t sustainable and I knew it, but was banking on getting budget for UX resources.

While I was helping the BA’s, Development Team, and QA by ensuring the stories had a visual component to help ensure we’re all on the same page of what the user story looked like, I’d end up neglecting other things like refining those very stories, not unblocking the development team when they’d get stuck on build or architecture issues, nor helping push the DevOps team to help the QA do their job.

Rather than complain, I made a daily tactical call on what to focus on based on what Trello was telling me. Once we got the UX resource onboard, he worked aside the BA’s and that helped a ton; at that point I could just match the design comps to his wireframes, cutting my work in half + his were of insanely higher quality for talent & focus reasons.

What this tells me is that unless I have a huge backlog of build and DevOps work in the pipeline, I’ll be hard pressed in the future to keep my development team busy with those tasks for a long time without quickly needing a proper UX team member(s).

QA in Lean Engineering

I didn’t have enough seniors to delegate management tasks to, and coupled with my CD problems, I struggled to keep QA productive. While our developers were using linting compilers, complexity metrics, unit and integration testing with end to end testing, no one was laser focused on improving the latter part of the QA CD pipeline. I’d made some headway in getting QA involved in the beginning to help contribute to ensuring good user stories came out of our workshops. Where I struggled was giving them enough of my time to teach them basic JavaScript coding, DevOps, and helping them walk through their testing plans on what we did have to start to develop a cadence.

A lot of this was we just didn’t have that much to test yet and the other was… well, nothing. I did the best I could working insane hours. If I were to do it again, I’d assign a senior dev interested in furthering their testing & DevOps chops to work with them on owning the CD process, and ensuring a good quality pipeline.

In Lean Engineering, QA is no longer thrown code to test weeks or months later. Instead, they are brought into the beginning of the process and the end to improve the entire pipeline. You can’t do that if you don’t have a DevOps pipeline.

User Feedback

The same problem I had with QA I had with user feedback. Part of Lean engineering with Kanban is continuously improve not just the process, but the software. You do this by giving the working build to a user, testing it, and taking their feedback BACK into the process. While doing wireframes, I did informal and adhoc user interviews, created basic Persona’s to differentiate who we were targeting, but did not get to validate this with released software until late in the cycle.

This actually wasn’t much of a bad thing, but rather, a challenge because a working build didn’t emerge until much later in the cycle, so we just did localhost demo’s & testing vs. “use whatever device you have on your person or will use in your job”. I had already had extensive, informal discussions with the target users and really liked them as people. It just came up when I’d look at swimlanes via colors in Trello cards, the features had a huge cycle time in knowing if they were valid or not from user testing.

Role Changes

Traditionally in Agile, I’ve found I do most of my management efforts on Sprint Planning and post Retrospective. I ensure the requirements are rock solid and follow up on loose ends, and take action items seriously during retrospectives where new things need to be implemented or changed. The rest of the time I architect, pair program, and code.

In Kanban, it was very different. My role, daily, was to manage away problems for the team. Instead of a weekly or bi-weekly discovery, this was daily to hourly. I’d adjust based on what Trello was telling me. It gave me a greater insight into how my management efforts positively and negatively affected the team.

I also liked continually working with the team to improve our process. I’ve done that before in teams with Scrum, but process improvement usually fell behind “getting my story done” in terms of priority. In Kanban, fixing the bottleneck and improving the process is the priority.

I’ve found I really like Kanban. The consulting world is full of extremely hard software problems surrounded by politics and chaos. I love those aspects and Kanban is now my tool of choice for managing teams within it.

Citations

I wanted to thank Joel Hooks for telling me about Kanban being an alternative to Scrum years ago. If Joel likes something, I typically trust his judgement that it must be good.

Also thanks to my manager, Matt Lancaster, for teaching me about Lean engineering processes. You can see him speak about the process below.

Thanks to Eric Motazedi for teaching me about BDD and why workshops are so important.

Finally thanks to the Richmond Capital Kanban group for teaching me more about how Kanban works.